All the new schools come with cafegymatoriums so I figure I’ll go with a 3-in-1 post.

Homework

For 12 years I had assigned it but it always bugged me that we would spend 15+ minutes the next day going over something that many of the students didn’t complete. And if they did bring it in, how did I know if it was actually their work? Now that I have children of my own in school, I am even more bothered by the amount of busywork that imposes itself on family time.

My question isn’t regarding the validity of homework. My question revolves around the idea of how to make homework matter. How do we make it meaningful to our students? Can we tie it to assessment and/or differentiate it so that kids can work on what they need at any given point in time? And further, can homework become part of a meaningful dialogue between teacher and student rather than a box to be checked on the daily “to do” list?

Assessment

Quiz, Quiz, Test. Quiz, Quiz, Test. Quiz, Quiz, Test.

Isn’t that how the pattern goes? Followed that one too. But again, over the past few years, my view of assessment has changed. When do we assess? How often? How many times should a student have to show us he can do something? How many different ways should he have to show it? Multiple choice or free response? Where does writing come into play?

For the past three years, we have been dealing with pacing guides and benchmarks due to the fact that my district is in program improvement. I am in favor of it. Pacing guides and benchmarks have allowed us to begin with the end in mind, check for understanding along the way and then find ways to intervene with students who are struggling to grasp the concepts/skills. However, I have noticed that teachers have a tendency to become very procedure oriented and lose sight of all the great thinking that can be provoked in a math classroom. I don’t blame this on pacing and benchmarks any more than I blame bad lessons on the tools being used in the classroom. It has become obvious that the textbook pacing isn’t the way we want to go, so we have started to teach one standard at a time. But I think that many of our standards need to be deconstructed even more in order to ensure that when we assess, we get a grip on where a student is really struggling. For example, in California, Algebra Standard 15.0 deals with mixture, rate and work problems. It isn’t enough to say that a kid is struggling with 15.0, we need to be a bit more specific in order to fix the problem. I know that Dan has done a nice job of explaining the need to break the curriculum down into skills and he has a great assessment plan. The part we have struggled with is what to do in between the initial assessment and the re-assessment(s). Which leads us to…

Differentiation

Is it enough to throw some review problems up on the board for warmups and call it “intervention?” Do we give students different assignments based on their need — and when we give these assignments, how do we grade them? How much weight do they carry in relation to the final grade? Can I actually have 30 kids working on 30 different things? If so, does that mean that I have to come up with 30 different assignments for each skill I want to remediate? My head hurts just thinking about it.

Until recently.

Why can’t we tie them all together? Why can’t homework/classwork be prescribed based on the results of an initial assessment becomming a prerequesite for the re-assessment; a key to unlock the assessment box. A student can be placed into one of two paths: the road to proficiency or the road to advanced status. Once a student reaches proficiency in a certain standard/skill, he earns a B. He then has the choice to move towards advanced status in that skill (for an A) or work towards proficiency in another skill. If he never moves onto the advanced path, the score for that skill remains a B. I am not sure if we should go with a 1-5 grading system or attach a percentage to the rubric score. (ie. 5 = 90%, 4 = 85%, 3 = 75%, 2 = 65%, 1 = 50%)

Over the past month, I have had some release days and have come up with a template. The challenging part has been to decide which “tasks” a student must complete before being allowed to re-assess. These tasks are very minimal in that they merely show what I would like a student be able to show before he is allowed to re-assess. Could a student take these tasks and “create” their own problems based on the template, or would the teacher need to be more hands on in helping direct the student? Are there skills I am missing? Are there ways to demonstrate the skill that I am leaving out? How can this be adapted for student interest and/or modality? And most importantly: does this idea stand a chance? I would really appreciate any feedback that I can get on this.

Note: Our math classes are in 94 minute daily blocks, so time for intervention/enrichment is built in. We will go with a sort of 60-30 model next year where we do regular instruction for the first 60 minutes and leave the last 30 minutes for students to work on their choice of previous skills.

The proficiency tasks for each skill will be followed by the student doing an exemplar. My working definition of “exemplar” is a problem that exemplifies the given skill worked by the student with written and/or verbal explanation of the process used. I have found these to be very good authentic assessments. The student has the option to do this via paper and pencil or mathcast.

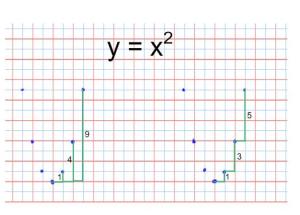

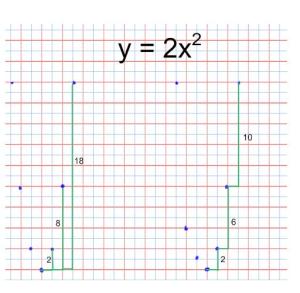

Simply use the stretch factor to adjust the relationships:

Simply use the stretch factor to adjust the relationships: This year I have given them choice on this, but it has caused a few kids confusion as they end up with a hybrid process. Next year? Not so sure.

This year I have given them choice on this, but it has caused a few kids confusion as they end up with a hybrid process. Next year? Not so sure.

Recent Comments